Historically, ship owners protected themselves from pirates with weapons. Today, criminals also use an arsenal of digital weapons to attack. And globally, the maritime industry is struggling to keep up as cybercriminals get faster and smarter. Fortunately, Europe is leading in the effort to bring cybersecurity to the forefront of an industry that has traditionally been resistant to change. A key example is La Marina de València, home of TNW’s first conference in Spain in March 2023. It operates as a Port 4.0 testbed and the world’s first cybersecurity Living Lab for the maritime industry. A look at the current status of maritime cybersecurity reveals an industry slow to prevent cyberattacks and struggling to keep up with the technical advances of cyber criminals. While cybercrimes present a number of unique challenges for the industry, Europe is leading the way as a valuable testbed to secure the seas by identifying cybersecurity vulnerabilities and preventing future attacks.

Cybersecurity and industry 4.0 at La Marina de València

The Port 4.0 project is the brainchild of the Valencia 2007 Consortium and Telefonica Tech. La Marina is home to around 1,000 recreational boating moorings previously managed manually (think wet paper and clipboards). Now there’s an app that allows boat owners to manage their vessels and bookings remotely and in real-time. The owners of the moored boats now also enjoy digitised electricity and water supply services. This tests 5G communications, signature and certification platforms, proprietary identity systems, blockchain, and cloud repositories. Anonymized data is generated and made accessible to select scientific and technical communities through an API for R&D purposes. And it’s a powerful way of testing the level of security of new tech in the wild. According to Sergio de Los Santos, Director of Innovation and Cybersecurity & Cloud Lab at Telefónica Tech, “being able to test our technology in real use cases, solving complex and specific problems thanks to our innovation, is a unique opportunity. Maritime organisations’ distributed and global nature makes them an appealing target for cybercriminals. Vessel downtime is expensive. This increases the likelihood of a ransomware payout to avoid disruption. And the problem is only getting bigger.

Maritime digitisation expands the attack vector

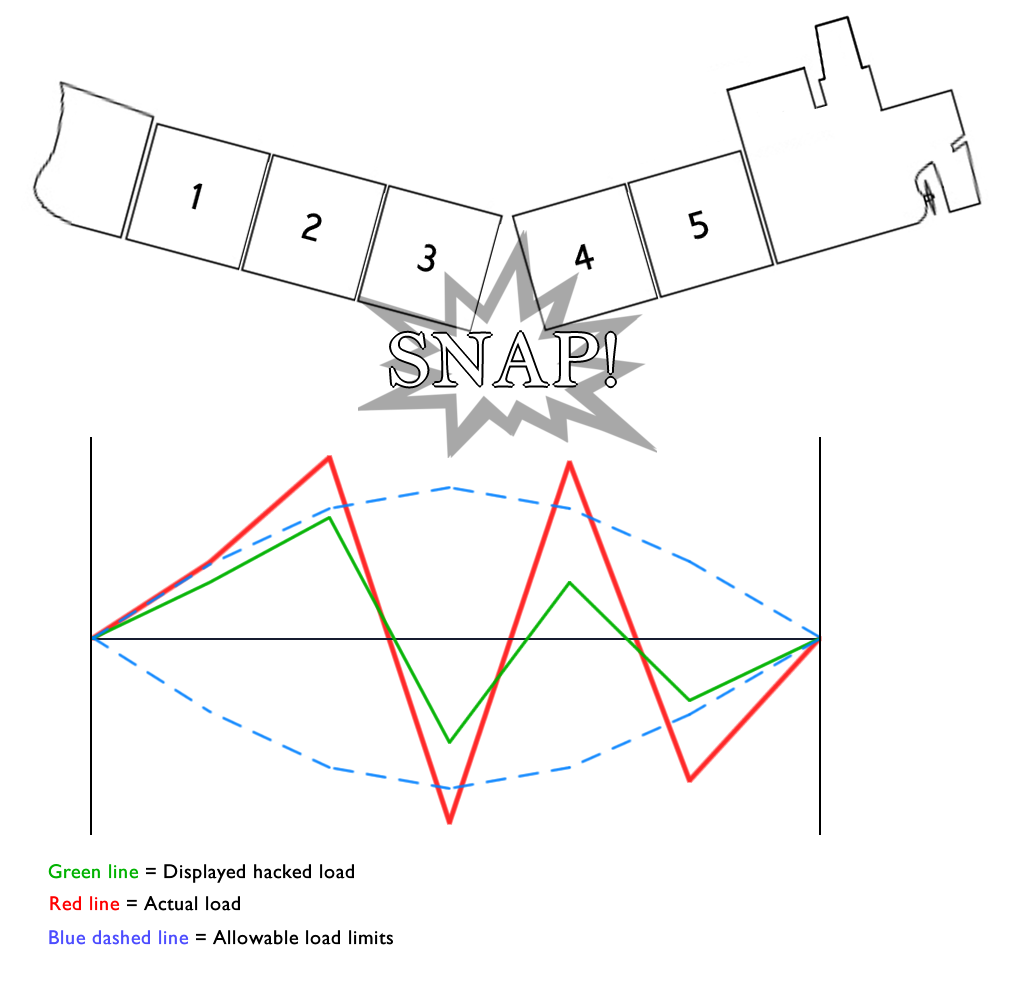

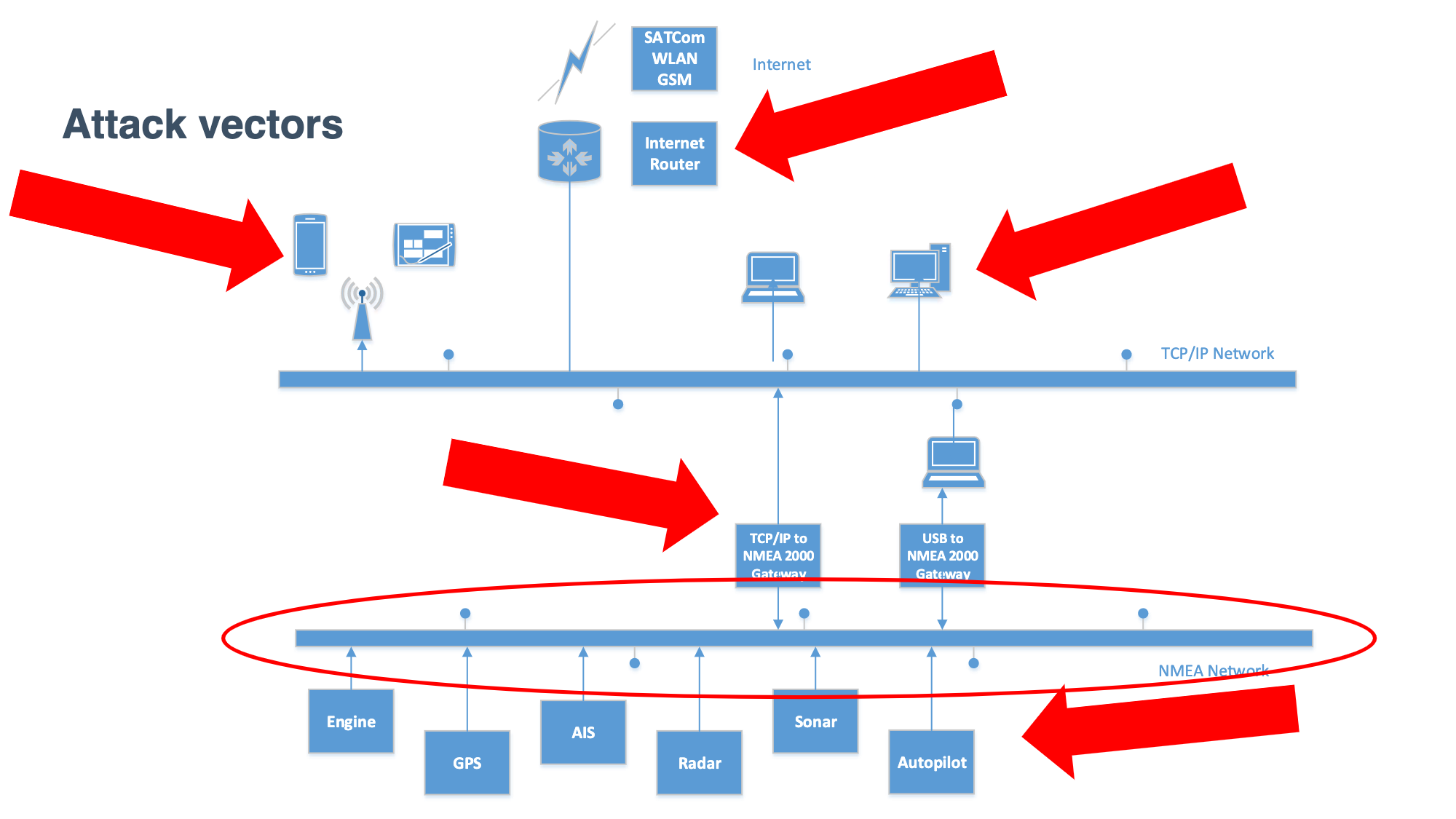

As ships get bigger, with more automation, fewer crew members, and more connectivity, the attack surface expands. A modern maritime vessel involves a complex plethora of digital and hardware devices. This opens the potential for cyber attacks both onshore and offshore. For example, manipulating loading data so that the actual cargo weight is inaccurate can potentially damage a boat or cause it to tip – particularly perilous if it is carrying cargo such as explosives. Hacking can be as simple as bringing onboard an infected USB drive or as complex as an attack on the internet router or satellite modem. The opportunities are huge. And there are a variety of different methods. Here are some of the most common:

Ransomware: Give me all your money

Ransomware is malware that threatens to publish or block access to data and computer systems until a ransom fee is paid. The maritime industry has been no stranger to ransomware attacks. The world’s largest shipping and logistics companies have suffered ransomware attacks, including COSCO from China and CMA CGM from France. In February this year, port facilities in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands were targeted by a large-scale ransomware cyberattack that delayed operations at oil terminals and crippled their loading and unloading systems. Even passenger vessels aren’t immune. In June 2021, the largest ferry service to Martha’s Vineyard island in the US was targeted by a ransomware attack affecting the ticket booking service and website. Notably, most ransomware attacks go unreported, with companies opting to pay the money (which leaves no guarantee attackers will release their data or resist the urge for a future attack). There is no formal legal requirement to report ransomware attacks increasing the challenge of preventing further attacks by monitoring cybergangs. In addition to a paid ransom’s financial gain, criminals may steal data they can sell on the black market:

Obfuscate or conceal your vessel’s identity

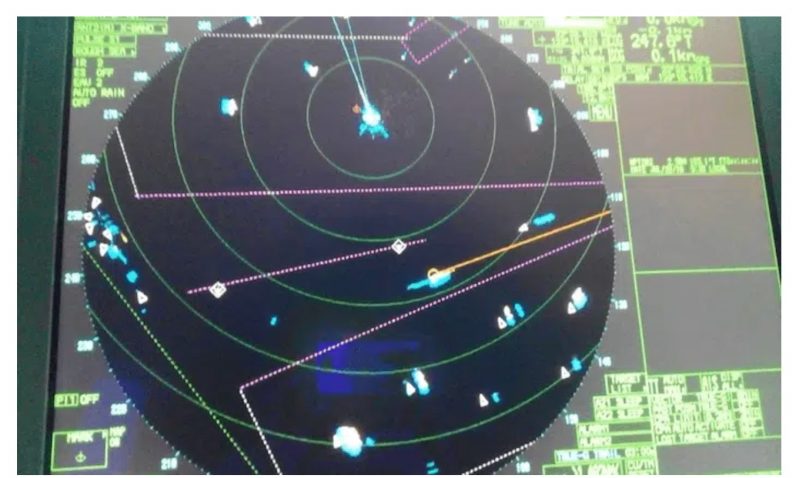

Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) enable ships to transmit small parcels of data such as a vessel’s type, identity, position, course, speed, and navigational status to improve maritime safety and avoid collisions. It provides a means to detect and prevent illicit activities at sea. AIS hacking also can misrepresent a ship’s location. Naval vessels are extremely attractive to cybercriminals. In June 2021, the AIS tracking of two UK and Netherlands Navy ships was hacked. AIS data transmitted that the vessel sailed from Odesa port to Sevastopol, within just two nautical miles of the Crimean port – an aggressive political act that would call for retaliation. But in reality, live camera feeds show that the vessels had never left port. A similar attack affected the AIS track of nine vessels from the Swedish Navy in February 2021, making it appear that they consecutively left the naval base in Karlskrona late in the evening and sailed south into the Baltic Sea when they did not. Bizarrely, AIS can also be turned off for vessel obscurity in unsafe areas inhabited by pirates, to mislead Port authorities, or conceal a vessel’s identity or route or criminal activity. This allows vessels to engage in illegal fishing, carry illegal goods, circumvent international sanctions, or gain a financial advantage – for example, oil traders concealing the oil by switching off AIS. This could affect crude oil prices.

State-sponsored attacks

As an industry, shipping is subject to state-sponsored attacks, sometimes as an intentional target and sometimes as a victim in a broader cross-industry attack such as the NotPetya attack that the CIA attributes to the Russian Military. Attacks like these are for political gain, whether to gain information illicitly or adversely impact another country’s economy. For example, in May 2020, Iran’s busy Shahid Rajaee port terminal was hacked. Computers regulating vessels, trucks, and goods flow crashed simultaneously. It resulted in a massive blockage of waterways and roads near the facility. It was allegedly by Israeli operatives in response to Iran’s cyberattack against Israeli water supplies. But perhaps the most infamous example of a state-sponsored attack was NotPetya. This military cyberattack masqueraded as a ransomware attack but, as Daniel Ng, CEO of UK maritime cybersecurity company CyberOwl explained, was actually a more aggressive lockerware attack, permanently wiping data. And it hit Copenhagen-based shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk, which moves about one-fifth of the world’s freight, downing the company’s digital infrastructure for over a month. This resulted in a financial loss between $200 to $300 million range and forced its IT team to reinstall the software on its entire infrastructure, including 45,000 PCs and 4,000 servers.

Activists

More common in industries like oil and gas and logging, activists can also cause maritime chaos by tweaking navigational data. In February this year, hacking group Anonymous renamed Russian president Vladimir Putin’s yacht “FCKPTN” by vandalising maritime tracking data. They also made it look like the yacht crashed into Snake Island, Ukraine, with the destination of “hell.” There are also a plethora of cyberattacks where the potential is less clear. For example, in February this year, the Port of London Authority was hit by a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) cyber attack by Iranian cybercriminals, allegedly a politically motivated attack. It oversees the movement of more than 200,000 commercial and leisure vessels annually. It’s unclear whether the act was political or a case of digital vandalism. It could also have been an effort to distract from a sneakier attack. Or the aim to disable systems that might detect such an attack. with love, #Anonymous ❤ pic.twitter.com/3T8BLAcVOA — Anonymous (@LatestAnonPress) March 1, 2022

Why is the maritime industry so slow to act?

The maritime industry has undergone a digital transformation for decades but lags behind other sectors when it comes to cybersecurity for various reasons. There’s good old ‘security by obscurity’, where companies fail at even the most basic inventory of their digital assets. There’s the combinatorial complexity of legacy and modern equipment unable to guarantee security. This is because legacy equipment is out of warranty and cannot be patched. Unlike the IT infrastructure, not all operational technology (OT) infrastructure has traditionally had a dashboard for operational visibility. Any anomalies, if detected, may be attributed to a system when they represent something more severe that then spreads to the IT network. The challenge of securing the seas is exacerbated by a lack of reliable end-to-end digitization. Ng shared that, for example, cargo vessels spend most of their time at sea, with only very short windows at port, during which they are otherwise preoccupied with loading and unloading goods. Ng explains, “Often the ship managers will decide, they’re just not even going to fix it. Or there’s just not enough time to do it.” And a vessel may get dry docked, in a position to dig deep into repair and updates, only every three years. This is due to waiting queues at docks. That’s a long time between in-depth security updates.

Insider jobs are also part of the mix

Insiders can also aid cybercriminals. A 2019 study by Red Goat Cybersecurity surveyed thousands of people across industry verticals and found a wealth of underreporting of suspicious activity. One shipping company employee recalled: Then, there’s plain old reluctance. de Los Santos, asserts:

Cyber-SHIP Lab

In 2019, the University of Plymouth launched Cyber-SHIP Lab, a national centre for research into maritime cybersecurity. It is developed in partnership with equipment manufacturers, solution developers, shipping and Port operators, shipbuilders, classification agencies, and insurance companies. I spoke to Lab staff member and cybersecurity lecturer at Plymouth University, Dr Kimberly Tam, who told me that the lab provides a unique hardware-based configurable test bed platform to replicate and risk-assess vulnerabilities, “like electrical loading, overheating, signal conflict/strength that you can’t in simulation.” The audience extends from students and government to manufacturers and companies who have experienced or are anticipating an attack. She explained, “We look at systems currently deployed, but also next-generation technology that hasn’t hit shelves yet.” Earlier this year, the research department worked with the Bank of England. They wanted to test how some of the world’s leading insurance firms would respond to a maritime cyber attack. They used a scenario where an individual or organisation gains access to the bridge system of commercial seagoing vessels. This caused physical damage to ships and ports. The maritime supply chain, accounting for 90% of world trade in goods, was heavily disrupted. Companies are then asked to detail their response and the impact upon their clients across various industries. It’s the first time a maritime cyber incident has featured in the General Insurance Stress Test, and Plymouth is the only university credited with helping to pull it together. In early September, Lloyd’s of London announced that their insurance policies would stop covering losses from specific nation-state cyber attacks and those that happen during wars from March 31, 2023. This can massively drive up the cost of insurance policies and leave the shipping industry significantly out of pocket. As Lisa Forte, an analyst at Red Goat cybersecurity firm, wrote, “it’s heinously tricky to definitively attribute attacks to particular groups or provide proof of state sponsors. Is there hope for the ships of the future?” In the short term, no. I asked Ng if I was a rich person and bought a brand spanking new high-tech boat with the latest software if it would be secure. He laughed, “not even close.” But fortunately, the tides are turning. The International Association of Classification Societies has developed two Unified Requirements (URs) on cyber resilience. They are mandatory for vessels constructed from January 2024: UR E26 aims to secure IT and OT equipment during a ship’s design, construction, commissioning, and operational life. Vessels regulations cover equipment identification, protection, attack detection, response, and recovery. UR E27 aims to ensure system integrity is secured and hardened by third-party equipment suppliers. This UR provides requirements for cyber resilience of onboard systems, equipment, and the user interface, as well as product design and development requirements for new devices before their onboard implementation ships. However, as Ng notes, this excludes the 70,000-odd vessels currently operating. In the US, a reauthorization bill called the “Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2022” is currently being pushed, requiring the Coast Guard to massively update their efforts on maritime security. Its focus includes data gathering and management for studying cyber threats. It also calls for limits on the procurement of specific Chinese technologies. Kimberley Lam is hopeful that we can meet all the threats in the upcoming years head-on and be prepared. However, she remains concerned about the influx of nation-state threats. She asserts: “We are seeing the start of this, and if this trends to more intelligent attacks in a world with more autonomy and complex systems, this is a danger.” And in case of the next attack, it’s a matter of when not if.